Standard narrative disrupted - the pioneering art of Hilma af Klint

The standard narrative of the history of abstract art has it that the Russians Wassily Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich, and the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian were the trailblazers of abstract art, producing purely non-figurative works in the early years of the twentieth century.

The story goes on in a linear fashion through other figures like Robert Delaunay and Henri Matisse towards the great abstract expressionists of the USA in the 1940s – Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko et al. A very boyo, macho epic. Now it seems the story needs re-writing.

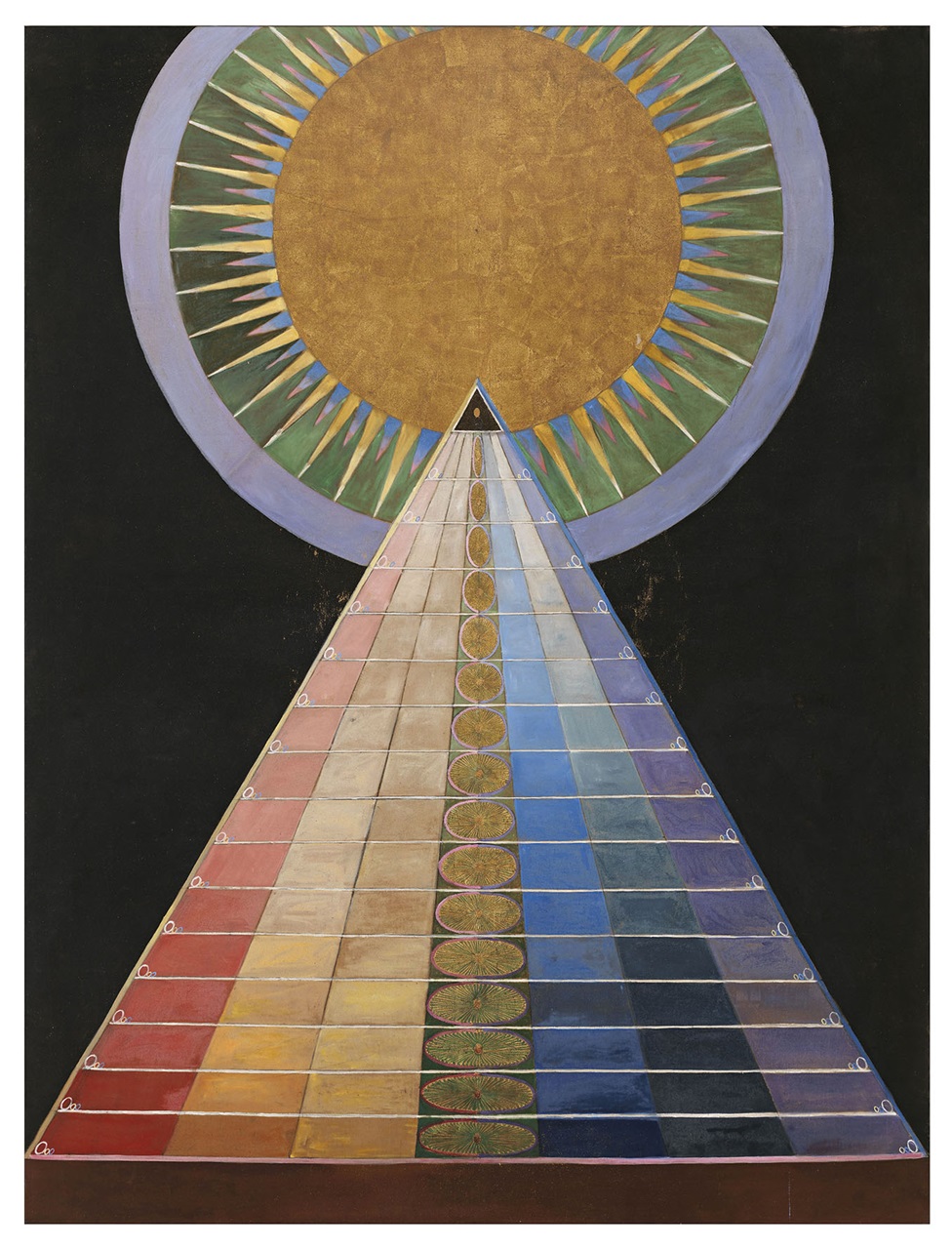

The first non-figurative artist, (in the Modernist Western canon at least) it appears, was a Swedish woman named Hilma af Klint, whose non-representational paintings predate those of any of the known protagonists.

Hilma af Klint belonged to a group called ‘The Five’, a circle of women who shared her belief in the importance of trying to make contact with the so-called ‘High Masters’—often by way of séances. Her paintings of these experiences became a visual representation of complex spiritual ideas. But because they worked in relative isolation, away from the art capitals of Europe, af Klint has been overlooked until now.

Her art career began conventionally enough: she studied at the Academy of Fine Arts of Stockholm, known as the ‘Konstakademien’, where she learned portraiture and landscape painting. She was admitted at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts at the age of twenty. In the years through 1882–1887 she studied mainly drawing, and portrait- and landscape painting. She graduated with honours, and was allocated a scholarship in the form of a studio in a building owned by The Academy of Fine Arts.

Throughout her career, her more conventional work, mostly landscapes, provided her with income. Her non-figurative work was a hidden secret. Her younger sister Hermina died in 1880, and Hilma at this stage embarked on something of a spiritual quest. She and ‘The Five’ became interested in the occult, and engaged in much discussion of the spiritual self, and organised séances.

As early as 1896, af Klint experimented with automatic drawing, something the Surrealists picked up on a generation later. She believed some force was guiding her hand in producing a purely abstract visual language. Her first purely abstract paintings were done in 1906. This was a series dedicated to a mysterious ‘Temple’, about which she had no rational explanation. Klint claimed that in a séance a spirit known as Amaliel addressed her directly, asking her to create the paintings that would line the proposed temple’s walls.

The paintings she created were monumental. All this occurred without any contacts with the contemporary modern movements. She wrote: “The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.”

The works were of value to her, and she retained them all her life, and in her will bequeathed them to her nephew. She stipulated they should remain secret for 20 years after her death.

When they were revealed in 1960, the cache of 1200 works re-wrote art history – but slowly. Even now, she is only a peripheral figure in the story of modern art. I’ve yet to find a book on the origins of abstract art that mentions her.

The collection was offered in 1970 to the modern art museum in Stockholm, which initially declined the gift. It was only an exhibition of af Klint’s work in Los Angeles in the USA in 1986, that gave her something of an international prominence.

What are we to make of Hilma af Klint’s story? Just that conventional narratives of history may overlook things, and that for those who look deeper, history can be, should be, re-written.

Hilma af Klint deserves a place in the history of modern art. She deserves to be a name we know.