Pigeon

Here’s how it starts: with a script. With an odd delivery. With coincidences, and inexplicable connections. With a mysterious something from way out left field flying into my already fogged-up life.

And, suddenly against the odds, everything in this life seems to be raveling again. But barely.

Friday, and a new client, one the suits had been massaging for years, literally, is finally bolted into our stable. Millions and millions in annual billings. Further international campaigns in the offing. This all happens at something past six (so, oh weary shit, I must stay on at the office), when I should have already been fighting the traffic in the rainy dark on the way home.

Make that ‘home’, with a very definite set of inverted commas. They look like horns. They are, I suppose, given what’s gone down to get us to this state.

Yer. So. A ‘home’ with horns – that’s what I would have been heading back to.

A home that is a cold, flat shoebox of aluminium and glass, daringly cantilevered over an upper arm of the harbour. With even a glass plate in the floor of the master bedroom, to see the tide beneath, and the moon reflecting on the water.

Her idea. From her cosmic phase. Most times it simply unnerved me, that glass floor, and later Frank the dog. Once, it must have bemused some late-night kayakers, who looked up to find us in flagrante delicto. When delicto still was possible. And laughter.

Only the foundations weren’t properly anchored (by a fashionable geo-architect of a few years ago, now exposed as a fraud, and living out a sentence at her majesty’s pleasure – so he’s not much help to fix it), and the whole hillside is moving anyway, and the entire shebang is tilting ever more daringly waterwards, more and more every week – I’ve taken to measuring the drift, if that’s what you can call it, obsessively measuring our inevitable and expensive slide into the sea. It all seems so symbolic. But the reality is, about 3mm every two months. Doesn’t sound like much, but inevitably the laws and gravity and physics will reach their new consensus in a frank and meaningful exchange. But for now, how the rest of the house still hangs on to the earth, I don’t know. What we do know is, this can’t go on forever.

So I’ve taken to wondering what kind of a splash we’ll make…

Make that ‘we’. Inverted commas again. Horns, again, also.

But, hey, it may make for good fiction. If I ever had time to re-start that novel. One of the many started, now in abeyance, while I work as one of the priests of sell-sell-sell. I’m an advertising copywriter and creative director for F&T, one of the founding directors (the ‘T’ is me) – and was good… before…before…this mess.

And the mess, it seems, has everything to do with Vicki.

*

She’s – where? Dunno. She’s not on these islands, nowhere in this country anymore, that I know. There was that first-class ticket out, one way. Eighteen months ago.

She’s – what? Dunno, again. I’m not sure anymore. She was my wife – right now, I don’t know what she is. Bryan her therapist is inventing, it seems, ever new and inventive and uncertain names for her cocktail of neuroses and disorders, one of which is to do, certainly, with compulsive spending.

She’s – got? A working credit card, a very hard-working credit card, a card last recorded working up a sweat somewhere between Portimão and Albufeira, in the south of Portugal. And on the statements (still delivered to me), some incomprehensible items for her, like giant glass balls, and carbon fibre arrowshafts.

She’s had two children, twin girls, ours, five years ago. Holly and Hazel. They’re – surprisingly (or am I sounding too cynical?) – lovely.

She’s had, she’s had – what? All the leeway our new life can allow. She’s had a thoroughbred. It bled money, like I’m told many horses do. (Though the filly’s lack of success did get us sympathy of a refined kind, from only those sophisticated enough to know the ‘pain’. Right now, I don’t know where the silly horse is. But I do keep getting the feed bills. Hazel says she wants to ride the horse someday).

She’s had a crack at a masters degree, abandoned it, she’s had intense time ‘in’, much time out, none of which helped.

She’s adopted another child, who is half ours. Her half. From that indiscreet moment – more like three months, the swelling belly frightened him off – of passion with the Samoan actor, which I so graciously ‘understood’. He’s three. The boy, Frank, that is. I like him. He likes me. We’re good fishing mates, almost ‘bros.’ We joke about that, and I do believe we both get the depth of irony inherent in that joke.

The actor is somewhere in California, working, last heard, on a pre-prequel to the famous science fiction trilogy. He has “no time to maintain contact – my career must take precedence.” Which is fine by us. He did leave a last, typically irresponsible present for the baby – a puppy. Which I now look after. I called him Frankie Too. I think the puppy scared him off.

She’s somewhere, physically, emotionally, spiritually. Apparently, she’ll tell us when she ‘arrives’. This intelligence is from her last email, two months old. No news since then, so I take it she’s still searching, and not arrived at nirvana yet.

But most of all, she’s left us all.

*

This is how our last conversation went. This, I avow, is a reliable record. It’s one of my things, I can recall word-for-word talks that have some import. And this one had all the hallmarks.

She is standing in the V of her car door, protected by it. He is sitting in the passenger seat, staring shiftily ahead, his one hand compulsively plucking at the seatbelt. He’s smoking, damn him. Later I learn he’s back from California, just for a week.

They are ready for me as I pull in the drive, home on a Thursday evening. There’s a light rain falling, spotting her cerise tank top. And then I see the suitcase in the back seat, her new Trelise Cooper jacket thrown over the seat.

V: Mark, I’ve done what I can to set things up –

Me: What things?

V: Kids, their school commitments, you know…

(I see faces pressed against a window)

Me: Hang on, I’m not quite up to speed…

V: It’s not about speed –

Me: Sorry. Start again. You going somewhere?

V: (she does her little half snort-laugh). Somewhere. Some Place. (A shuddering sigh, and an earnest look at me) Some time.

Me: (slowly dawning) Oh shit. He going with you?

V: No, just dropping me at the airport. He’ll bring the car back. But he needs it for a week.

Me: (simply gulping)

V: Love…love is flight, you know Mark. And navigation. Oh, god, what am I saying? (Long silence) I’ll call.

Me: From where?

V: Don’t know. (In normal conversation she says ‘Dunno’. This was two distinct, hard words.)

Me: When?

V: Wish I knew.

Me: Wish I knew, too.

V: Fuck, I wish I could have done this better – (she stop abruptly, she’s turning to fit her shoulder into the wedge of the opening of the car door)

Me: Vicki –

(But she slides downwards into the car, shuts the door gently, and reverses out of my life.)

There. The transcript is so flat and ugly, it reflects accurately the banality that serves as dressing for our lives. Even her attempt at profundity with the navigation thing fell flat. As did my attempt at dramatizing the situation. It was all over so quickly, so unsatisfyingly. It feels like an end with no explanation.

The note in the bedroom doesn’t clarify much further. It’s just like a rehearsed replay of what was said before. It says.

Dear Mark –

This flying is my form of love.

I must navigate my way to my god. (lower case).

I know you’ll do well with the kids.

Love, always, but not sure,

Vicki.

The note, for chrissakes, is typed. Even her name.

Fucking terrific.

*

I tear up the note slowly, piece into smaller pink piece, and scatter this sad little bundle of confetti into a bowl of potpourri on her dresser. Always hated that stuff. Too twee by half. I notice her cosmetics are all gone.

(Sometime later, in a further fit of pique, and goaded by Longshaft, Frown and Aaron, that mix gets tipped to the fish smoker. It makes a fragrant smoke, but that kawhai tasted odd.)

*

And I have three frightened little faces to face. I say she’s on an adventure. Like Tintin. And that she’ll be back. Only, like her, I’m not so sure. And neither is god (lower case) either, I suppose.

*

And that is the brief update of the situation with Vicki, my erstwhile, ever searching, not-quite-arriving wife. Here’s hoping her navigation will come up to speed.

*

And I’m – I’m about to leave the office. I’m living in this present. Someone has to keep on keeping on, for all of us. So it’s me. And one more way of keeping my art unattainable.

But at least the mess she’s left me with, keeps me well versed with the ‘time pressure of modern living’ (my worst line ever – but hey, it worked), into which I must sell more things to help each of us cope. Maybe that’s why I became good at it. But now I’m deep dog-shit tired of it all. I’d happily expose my sham, my hatred of it all, but must keep on acting.

I’m about to leave the office, half-jacketed, arm in one sleeve, car keys clutched, papers clenched in lips, rushing as always.

I’m thus, posed, poised, caught contraposta, as the account executives sweep back victoriously to the office. Awkwardly, I am swept backwards. I spit out the papers, deposit the car keys, shrug off the jacket, follow them into the boardroom.

Debrief we do. The Bollinger abounds. We wet the ceiling. We wet our whistles. We wet our appetite for more winning creative. Of which I can always supply. Always could. Now back on form. We toast me. Good for me!

We ceremoniously anoint our new flagship product, a one litre white PVC handled bottle, standing lone and proud (there are dozens more in their line, all established market-leader consumerables, gold-plated brands but this one is new, our test), standing alone in the middle of our boardroom table.

The evening elongates. I embrace suits, good boyo bonding. I drink more. I laugh uproariously. I kiss G (short for Gin, short for Ginevra, it’s Italian) in the office kitchen. She kisses back, briefly, something cold pressing in my side and the small of my back, then says, “Just came here for these few more,” waving the Stoneleigh Pinots Gris.

She releases them, puts them on the shelf, for a better reach around me, another quick hug, then spins, and pirouettes out.

I phone Mum at home; “Don’t worry about the kids,” she says (and she, lovely loving warm generous ageless even-spirited she, means all three), “All tucked in, fed and read.”

I smile briefly at this, the most reassuring of her repertoire of kids’ catchphrases. I have the obligatory short moment of parental guilt, then just a quickly rationalise that they, the kids, are better off with my mum, perhaps, than theirs. So that leads to a quick flash of anger, but something not for this time and place. It would be futile, right now, and expend itself against something greater, something vast, turgid, inexplicable, oceanic. That anger would just expend itself against itself.

So I snatch the bottles from the office kitchen shelf where G left them, like markers, and waltz beamingly back through to the noisy boardroom. I feel like I’m walking through layers of cling wrap, away from that last, homely, reassuring phone call. Layers of wrap, sticky, yet clear; and it just as surely seals behind me. And I think of the times I have left my children, un-tucked-in, un-fed, un-read in that strange, cold, sliding-down-the-hillside house of ours. And think of what I must do to keep this flawed show on the road.

And I catch myself thinking, “All this for a fucking bottle of toilet cleaner.”

*

We started this agency in the mid eighties, Mark and I. Two Marks, Mark Town (me) and Mark Frown. You can imagine the debates about the name for the company, but in the end settled with F&T. (Subtitled, on occasion, Friggin’ Triffic), and known in the industry as the Frown and Town show. Of course, business journos have had great fun with the names, over the years.

We’ve been successful. More than moderately so.

So why did Vicki flee? Maybe I shouldn’t ask that question too carefully. The answer could be all too obvious.

And now the Town and Frown show must continue. It’s the thing we have wrapped ourselves in.

*

This is where it starts. Our long and fruitful relationship with Sunbright starts right here. With a toilet cleaner. As yet unnamed. And for which I must have an identity, nay complete personality, along with campaign strategy by next Monday morning. I take the bottle home; it sits snugly, smugly, sticky with dried champagne, in the leather fold of the SAAB’s seat (‘Ugly car, ugly bottle,’ I’m paraphrasing an old line for gin – can’t use it here). The bottle is a small sick-smelling ghost in my presence, a miniature malevolent Casper. God how I long for ghosts that are friendly, at the very least. The white litre bottle - it illumes in the wet-night-swishing dark of the car. It lights up, rhythmically, a dull orange glow, from passing street lights. It hums along with Phil Manzanera who is playing on the CD. It follows me indoors, when I arrive, tiptoe, so as not to wake – even my Mum, who is wheezing gently and dribbling demurely in front of the telly. I shake her softly, wake her, and she smiles dreamily and pads off to the room she uses at this place.

It gets underfoot on Saturday outings. Then it shares my bedroom. I try a bit in the ensuite. So I suppose it spreads its little bit of Sunbright into the harbour, via our sate-of-the art aerating system. It stares at me all weekend, and all through a week that vanishes.

Till Monday. The next Monday.

Which is now. And the Sunbright meeting is in two hours time.

I grump past Intella Hobson, front desk (we call her the ‘Director of First Impressions’ and she does well in that regard). Pick up my mail, plump down at the desk. It’s late in the morning. Head hurts.

A paper aeroplane is tacked to my computer screen – nose deliberately bent. It’s the other Mark’s way of sending messages:

Let's talk about the Friday night awards.

After the Sunbright thing

– let’s learn to win

again!

M.

I wince again, roll eyes skyward. And wearily reach for a coffee cup.

First, the mail, e- and otherwise. It’s an old habit of mine, now even more acute, given the possibility of an explanation, a note, anything, from somewhere in the far south of Portugal. I skip the recogniseable mailouts.

Just then, Intella comes in, bearing a box, about shoebox size, oddly light, and from which emanates a soft scuffling noise.

It is wrapped in brown paper. It has holes poked in it, with a pencil. It is tied up with old-fashioned hemp string. It is addressed to me.

It has a smaller envelope on its side, tucked in under the string. It says, “Read please, don’t delay.”

The note inside says:

In this box is the answer to your Loo Blue problem.

Read it and see.

And then, if you’d like to hear from me again,

just throw the flyer out of the window;

and I’ll get back to you just when you need me.

OK?

For once, I slow down. I sit bemused. I mull over the note. I pick at the envelope it came in.

It’s an old-fashioned letter in an old-fashioned envelope, thick, orangey manila, with a white label pasted on.

I can see the label is pasted over many others. My name is enunciated in the most precise handwriting I’ve seen for years, written in what’s obviously an ink pen.

There are a few spots around sharp corners in the characters, as if the nib has snagged, and flicked a fine spray of ink ahead of itself.

And then I realise: this was written with an old-fashioned quill pen!

The envelope has a pleasing weight, and solidity. I heft it, turn it over: nothing on the back, no sender’s name, except for a curious outline, something that looks like a stretched, though incomplete, turtle. Like a rough monogram. Done with the same pen.

So to the box. The scurrying continues from within.

Then comes a sound, the unmistakable soft liquid call of a pigeon. In its gentle way, it says: “Hey! I could use a bit of light here; a bit of air; some flight, and freedom to return to where I came from.”

And I think: What am I going to do with a pigeon in the office? Of course I’ll toss it out the window.

With a quick flash of irritation (they’re all too common these days), I realise I’ve found myself in an elaborate entrapment. Is this another clever promotional gimmick? If so, then my SOH will expire. This on top of the complicated entrapment as engineered by Vicki, which is wearing very thin too. Entrapment. It has become a familiar feeling lately.

But this entrapment, now, is in a way that I’ve never experienced before. Somehow I see the element of charm in it. So a rueful smile breaks through the crust of tetchiness. And that’s something that new to me too.

Is the bird alone the answer to my Loo Blue problem, as promised? Yeah right, the cynic in me kicks in. Or is there something else in there? Something that could be useful?

So I peel back the brown paper, gently lift the lid of the old shoe box. A pigeon, tense, expectant, looks back at me.

I can see another envelope under the bird. Only one way to get at it.

So I cup my hands gently about the bird. I admire its colouring – pure white primaries and tail feathers, pastel liver mottling on its back feathers, and its head in a darker form. Intensely bright blue eyes.

The bird is warm, and frankly, quite lovely. It doesn’t struggle in my hands, and cocks its head to look at me. It’s more alert than any creature I’ve encountered.

And I can see it’s an athlete. It just wants the freedom to fly again. Back to where ever, and whoever, sent it.

But the windows don’t open in this air-conditioned building.

So I wander through the office, reverentially cradling this precious cargo, past the front desk, picking up a few interested hangers-on along the way.

In the carpark, I hesitate. Smile at my small crowd. Some window washers join the fringes of the group. Then I lift my hands together, opening them at the apex of swing, in a kind of supplicant gesture. The bird explodes into wingbeats, the first few of an impossible arc, seeming almost to touch wingtip-to-wingtip, above and below its proud little body. Chest out, all power, it rises above me, near-vertically for the first instant, then gathering force forward, faster and faster. I appears to be at top speed after only half-a-dozen wingbeats.

“Better acceleration than the SAAB,” I remark ruefully, but no one hears me. We are all enraptured.

It is extraordinarily beautiful, but within seconds it is gone, flying purposefully upwards.

The bird circles the building twice, traveling ever faster. I’m aware of our heads spiraling in unison as we watch it, fixated.

Then it heads out over the harbour, and out to sea. The moment is over.

*

We are quiet. Cedric Longshaft provides his brief trademark snort. Which translates as, “How ‘bout that – whatever it was.”

Frown purses his bottom lip, and tries to follow the birds flight, shading his eyes with an Economist magazine.

Intella starts an uncertain, one-person applause, but stops half-clap when no-one follows. She shivers her two upright hands, with a wistful smile at me, and I remember she was once in a kapa haka group.

We troop back inside. Gin heads off for another latte at the café opposite.

*

Sitting on my desk, an empty box that until a minute ago housed a pigeon. And in it, another envelope, and inside that…

…laid out, and annotated in exactly the way I had come to insist on, all caps (so the reading of it is measured) with even the words to be emphasised, underlined. Only all hand-written, in that same confident, feminine hand.

A script for a 30 second spot.

LOOK. I COULD WASTE YOUR TIME WITH SUNNY-SOUNDING CRAP ABOUT THIS STUFF

BUT THE TRUTH IS,

IT’S TOILET CLEANER.

SURE, IT’S WELL MADE, FORMULATED BY THE QUALIFIED PEOPLE WE PAY TO DO THE JOB.

PROPERLY.

AND, NO, THEY DON’T ALL WEAR WHITE LABCOATS.

YES, IT’S PLANT-BASED, AND SO IS BIODEGRADABLE.

NO, IT’S NOT TESTED ON ANIMALS.

AND YES, OF COURSE WE SOURCE THE INGREDIENTS FOR IT IN A SUSTAINABLE WAY.

THE PACKAGING IS RETURNABLE

OR RECYCLABLE,

BUT THAT’S UP TO YOU.

YOU KNOW THE RIGHT THING TO DO.

SO I SUPPOSE

I COULD ANIMATE LITTLE

GOBBLY GREEN MONSTERS

TO INHABIT YOUR TOILET BOWL,

MAKE A CATCHY JINGLE,

JUST TO SELL THIS STUFF.

BUT I THINK WE’RE ALL TIRED OF THAT OLD SHIT.

AND FRANKLY, I’M NOT KEEN TO INSULT YOUR INTELLIGENCE.

IT’S TOILET CLEANER.

IT WON’T HAVE A SILLY NAME.

JUST THIS LITTLE SPIRAL LOGO ON THE BOTTLE. SO WE CAN ALL SAVE A LITTLE TIME.

IT’S TOILET CLEANER.

WHAT CAN I SAY? IT WORKS.

BUT IN THE END, IT’S JUST TOILET CLEANER. IT PROBABLY WONT CHANGE YOUR WORLD.

JUST BUY IT.

PLEASE.

*

Here’s the coincidence. Not that an anonymous script landed on my desk, the very morning I needed it, on the very subject I needed it to be on.

No, it was that the mood of this writing was just so apt. So exactly like I felt that morning. So oddly honest. So different from my normal writing, as one of the many and ardent pimps of materialism. So removed from what I had set out to be.

I had dreams of writing that mattered, all those years ago. Dreams that died, and dried into a floppy disc (that’s how long ago!) resting in the top drawer of my desk at home. The desiccated remains of a collection of short stories that would re-define the genre. Stories about people in unresolved circumstances. (Ha! That’s a laugh. Disc duplicates life). That reminds me – I should save it and back it up, before that lonely computer disc slides into the sea with everything else. Or I could just start the stories all over again. And the novels, started and halted. Maybe if I could start on them again, they’ll have a new heartfelt pain this time, more authentic.

But that script, it was as if I looked into the lens, and spoke as if to someone on the other side of the world. Someone who knew. (Another thought: how did she know? And how did I know it was a she? I scanned the notes for any clues, but there were none.)

But then, old instincts kicked in. Two words. There were two words that didn’t quite fit in that script.

That PROPERLY. That PLEASE.

They jangled. Too needy. I reached for a pen, scribbled them out.

Then I dutifully scratched out the words ‘CRAP’ and ‘SHIT’, and replaced them with blander words I know the Advertising Standards Authority will allow for prime time air – ‘BUMPF’ and ‘GARBAGE’. Which is a pity, because ‘CRAP’ and ‘SHIT’ (in caps) were just fine for the job.

Now the script was perfect.

I could sell it to anyone.

The concept nailed. Mental high-fives prevailed.

And so I sat back and sighed. Me and an empty box in my office. And a script that worked.

I kept the box. Took it home for Frank, and Hazel and Holly. (You’ll notice I use their names in a different order each time, to avoid any hint of favouritism – it’s a quirk of mine.)

They loved the story about how the box with the bird inside came to me, and how I set it flying home. So did my Mum, who sat in on that evening’s story-telling, a rapt look in her eyes. She even clapped excitedly as the bird took off. Holly was misty-eyed. And I must admit, I told the story well.

The kids even gave the pigeon a name. They called it Munts. Privately, I thought the bird was too beautiful for that kind of name. But hey, irony abounds in this weird new world of ours.

And we all went to sleep a little easier that night. And for me, not before I retrieved the disc of old stories, and put it in my laptop bag. “There must be an IT boffin at the office who could open it for me,” was my last thought before sliding away...

*

All I can remember of her is the dry spot in her skin, halfway down her backside cleavage. Where my hand used to come naturally to rest while settling to sleep. And from whence it would migrate. Once upon a time.

Where is that little dry spot now? What does the climate of the south of Portugal do for little dry spots on otherwise beautiful nudes? God only knows.

Damn these dreams!

Vicki, Vicki…that’s the problem with chemistry. You can be irritated to smithereens by woman, this one woman in particular, and still you yearn for her with an unstoppable force.

But hey, you’re still allowed to get majorly pissed off too. That’s chemistry both ways, I suppose.

So in the ever-amending wordscape I live in, the word for her becomes cruelly truncated. I think of her now simply as V. This was never a nickname for her when she was still here – it’s come about recently with the scary aliens show on TV. The Aliens are V – for ‘visitors’. Their leader (it seems to be TV code these days for bad guys) is a coolly beautiful, but faintly reptilian-looking woman.

*

You don’t even have to ask.

Of course we used the script.

Without those two pesky P words. And minus the naughty C and S words.

And of course the client loved it.

There was the usual hush after the first reading of course – it’s all part of the theatre we provide.

But after the hush, ah, how we live for that gush. And it came, alright.

First in the form of a slow, dry nod, then a lifting of eyebrows, then a glance across to his executive-on-special-assignment (his lover), then a distracted fondling of the sample toilet roll on the table, left there as a centerpiece to our props, then a “Yes.”

A simple, spoken “Yes”. An emphatic Yes. And then another from her. A perfect pitch.

“Oh sheit,” was my thought. Another night celebrating.

I automatically reached for the phone to text my Mum that I’d be late. Again.

*

The packaging with just the spiral logo was a hit. Though the product did get a silly name (for the client, and radio – it would have been stretching the bounds of normalcy to have the toilet cleaner called ‘spiral logo’). So looking back to that first message that came with the bird, there was another thing the writer knew. And yes, the name did become Loo Blue.

The actor who spoke the lines, went on, within a year, to win the local gong.

The ads themselves swept the board at the local awards. Then took off to the World Advertising Awards in Cannes. And won there too.

I got my face on the front page of Ad/Media. And won creative director of the year. All on the back of that astonishing Loo Blue campaign. Which just got better with each new ad.

People started to call it the ‘new realism’ in advertising. A new signature style for F&T, no bullshit anywhere, arose in all my campaigns. Our campaigns. And they kept on winning. We were on a roll.

‘Telling it like it is: Selling it like crazy’, ran the legend on a cover story on us in Australian Marketing magazine. And unlike with other creative fashions in the game, copying us wasn’t really an option for the other agencies – it would have been all too obvious. Of course a few lesser lights tried, and inevitably failed.

Only the birds and I, and the mystery woman, had the touch that worked.

But the bird – that particular bird, Munts – never came back.

Other birds did. At irregular intervals, and always when I needed them most. Usually with just the words I needed, always bang on target.

I always used the bird-delivered ideas. They were just so bloody good.

Only one rankled – but it still worked. And the part that bugged me was private (well, sort of, in our too-intimate office). That script was for Tete-a-Tete, a new upmarket dating service.

It began:

IT’S NOT THE LONELINESS THAT HURTS,

I KNOW.

IT’S THE RANCOUR.

BUT, HEY, TIME TO MOVE ON,

AND STUFF HER/HIM ANYWAY…

YOU DIDN’T DESERVE THIS,

BUT YOU DO DESERVE A NEW MILIEU.

AND WE’VE GOT IT.

Etc…

And it was easy to make a cover story as to the ‘why’ of the birds coming. I invented a racing-pigeon-fancier friend, who I said needed to train his birds before big races. Everyone believed me. What did they know – or care – those busy and silly urbanites in our office, about pigeons anyway?

After the third bird arrived, nobody even bothered to watch me do the releases. Novelty expired. Two times watching was enough. So the birds, and their releases in the carpark just became part of the office routine. But each moment was as profoundly joyous for me as the first, the first time I threw the bird up into the air, saw its energy explode into urgent, aspirational wingbeats, felt the light flutter of its feather wind in my face, saw it rise, circle, and then recede into the limitless sky, beating purposefully and directly out across the Gulf.

The second bird I scrutinised carefully. It was a classic grey, with the two black bars across its secondary feathers, but handsome still. You might have thought it was an ordinary street pigeon, if it wasn’t for its supreme conditioning, its crisp alertness. When it took off, it was like it was in its own race for the record back home.

It had a metal band on its leg, with the letters embossed PWPC. Papaniu Workingmen’s Pigeon Club, the detective in me finds out, from a list of New Zealand pigeon fanciers clubs. But with an asterisk in the list, denoting the club is ‘believed to be non-active.’

Other birds come bearing different bands, and all from the asterisk list, all ‘non-active’ clubs. CTFC – Central Taranaki Flying Club (I loved the vicarious assertion in that). KKTPC – Kia Kaha Tonu Pigeon Club. WOA – Wainuiomata Pigeon Club.

I gather there are still 56 pigeon clubs in operation in New Zealand, including the Nelson Invitation Pigeon Society. I wonder what it takes to be invited. I muse, idly, if the pigeons are members of the clubs too? I am becoming distracted. A good thing, I suppose.

The only thing that changed is that Intella Hobson, director of first impressions, would handle these packages with a growing and reverent care, always holding them with both hands, level, and not moving rapidly. She’d set them down, and retreat, walking backwards (it became her little in-joke) with fingertips pressed together, fake-Bhuddist-like. I tolerated it, even began to enjoy it. I think she even thought she was getting somewhere with me. Well, good luck to her.

The scripts, the concepts, the sketches, the strategic ideas – they were all my secret. And they all worked. They were bloody marvelous – Friggin’ Triffic – without exception.

*

Once, a bird, a smooth chocolate brown all over apart from white primaries, arrived on its own. It flew straight in, through the front door, and perched on Intella’s desk, head bobbing daintily.

She brought it to me, holding it lovingly.

It had a note, written on impossibly thin paper (which I had learned is called a flimsy – lovely word), in a small tube on its leg. It said:

Not many do the trip both ways.

So, I’m special. A bird of both worlds.

If it looks like a hard trip back, I’d appreciate some safflower seeds,

or peanuts.

For an easy flight, just some dried peas, please.

If I could head back later this afternoon, that would be fine.

Another mystery. How does she get a bird to fly both ways – and right into my office? It’s possible, I know, a homing pigeon with two homes, but rare.

“Perhaps it’s a Superpigeon,” says Holly that evening, when the story is out.

“A maestro,” says Hazel. Her new favourite word.

“Clever-clever bird,” says Frank, flopping down on the dog like a miniature wrestler. Frank Too just farts.

“I love mysteries,” says Mum with a sparkle in her eye, stirring the soup.

*

My new hobby – apart from working on the manuscripts – was getting to find out more and more about pigeons. I even passed up on a scuba trip to the Poor Knights with Mark, Cedric and the gang (on Mark’s big new Martimo 550 launch), to go to a pigeon-fanciers show in Kumeu. I like new stuff, and was falling for this, big time. A nice diversion, and the kids loved it. We even thought about establishing a loft at our place – got the plans to build one from an old Popular Mechanics from the library. Haven’t actually started banging in nails yet.

Of course it didn’t take long to discover that from 1897 to 1908 Great Barrier Island had a regular pigeon-post service to Auckland, complete with the very first airmail stamps in the world. These stamps are now exceedingly rare, with only three known to exist – but in the pedantic world of serious philately, they are not considered real stamps because the service was not an official part of New Zealand Post.

Initially, the service was one-way, with the home base a loft in Auckland (I wondered if it was near the office of F&T). The working birds went back to the island on a steamer every week.

Up to five messages (including shopping lists – but probably no advertising copy) were written on lightweight tissue paper – known as flimsies – and rolled up in an aluminium capsule attached to one leg. I spend some time daydreaming what that job would have been like, receiving the birds, lofting and feeding them, reading the messages and passing them on the appropriate people.

The birds usually covered the 92 kilometres in less than two hours, but a record was established by a tall poppy pigeon called Velocity who flew the distance in only 50 minutes – an average speed of 125 kilometres per hour. That’s faster than you or I could get to the Island, once we’ve driven to the airport, waited for the plane etc.

I wonder if my birds have names, and start giving them my own. And speculate if Velocity 2010 (OK, not very original) makes similar time to her namesake at the turn of the century. Do cellphone towers, radio and other waves, GPS stuff beaming down from satellites into the now-crowded Gulf affect their navigation? I know electrical storms do – so once withheld the launch of a bird, a glossy all iridescent black, until the lightning over the Hunuas had subsided. Still, I noticed Douggie (named after the luckless winger, he looked that fast) made a wide curve around the remaining cumulo-nimbus clouds. But he must have got back, because I saw him again a few weeks later. Good ol’ Douggie!

A sepia three-cornered stamp, with a pigeon in the middle. There’s heavy symbolism in that, I chuckle grimly. Three corners, connected by the bird. I get this image enlarged, and installed above my desk at the office. Intella immediately says she likes it. Even Frown says something positive about it. G, for some reason, refuses to comment on it.

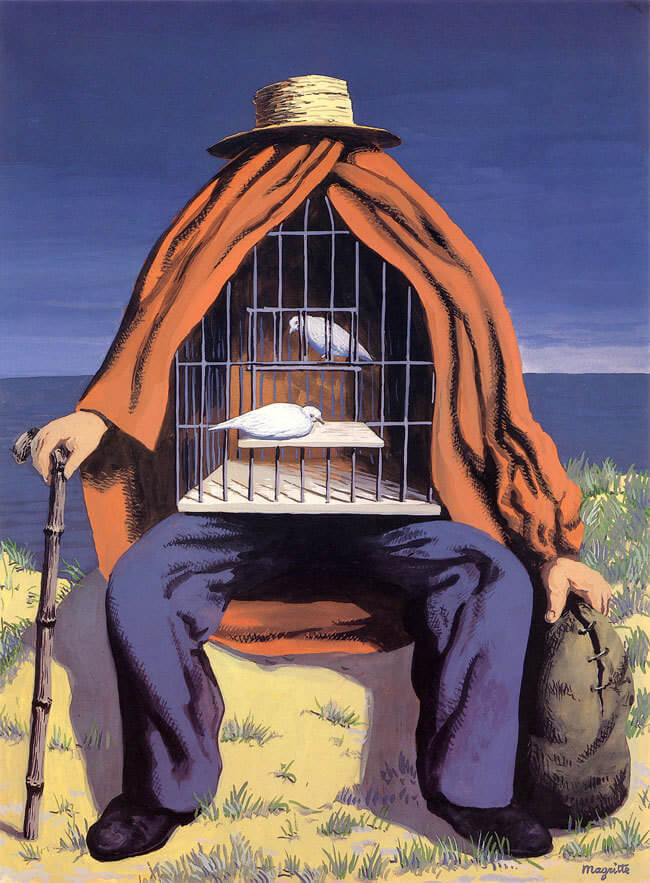

On the opposite wall, and despite myself for I think the painting is corny, I put up a print of Magritte’s The Healer. The two triangular shapes talk to each other, over my head. Perhaps, I reckon, it’s the Magritte picture that upsets G. The bloke has no eyes.

I prick one bird to get a blood sample, and find it, and all my birds, are of a breed developed in Anatolia, a breed renowned for their speed and grace, but notoriously difficult to breed successfully in maritime climates.

I take to calling the kids squabs – which is the name for baby pigeons, and a pretty groovy word too. Usually there are two squabs in a clutch. Squabs even finds its way into a bit of copy – well, was delivered in the copy – for a Christmas present waterslide thing for kids. It doesn’t take much explaining to get the word accepted in the script. It seems to fit, and I didn’t even have to belabour the pigeon thing.

I get offended when someone – I think it was Cedric – unoriginally, calls a street pigeon “a rat with wings.” I correct him – it’s proven that pigeons cannot transmit bird flu, although they are susceptible to a lesser strain of it themselves. They get sick from us I say, not the other way round.

I learn that homing pigeon will consider a loft they have lived in for more than six week, their new home base. Which triggers a curiosity: and so I traverse the credit card statements from my roving wife, and find Vicki moves on from each place she has found, always after five weeks, and always before the sixth week is up. I’m sitting there late night, alone with a merlot and the printouts, and my Mum snoring lightly on the couch curled up – I can see the soles of her feet facing me – and I become aware of Paul Simon (her choice of CD) singing sotto voce

There’s a girl in New York city, who calls herself the human trampoline, And sometimes when I’m flying falling tumbling in turmoil,

She says whoa,

So this is what it means…

I frequent second-hand bookshops (surprisingly, I find a few good ones in Hamilton, a city I had always written off), in search of the classics The Pigeon, (published at the height of pigeon fancying – 1958. Hey, that’s the year I was born!) and The Encyclopedia of Pigeon Breeds, by Wendell Levi. But sadly, these gems say in a mythical world. I had imagined they’d become the Ashley Book of Knots, to The Shipping News of this story.

But I do enjoy Andrew Blechman’s Pigeons: the fascinating saga of the world’s most revered and reviled bird. I agree with the New York Times, “For once a subtitle that doesn’t exaggerate.” I especially like Blechman’s dedication in the front of the book: ‘For Lillie Annabelle. I love you to the moon and back again.”

About which time I see V has spent up large on one of those weightless flights, where you get in a jetplane and they do a great high-speed arc in the sky, and a for a brief few moments you’re floating in a kind of padded cell. One of her very rare postcards (only the third in eighteen months) comes with a scene of her doing this. It must be a part of the package, along with the video I see she ordered. On the back of the card she has written:

M –

Me, floating. Fun!

V

Ps I thought of you while doing it…

Plenty of other books come my way, though. Suddenly, people know what to buy me for Christmas – two weeks ago I got three pigeon books under the tree. And I was genuinely pleased at each – though Patrick Suskind’s novella The Pigeon, I find strangely unsatisfying and unsettling.

But I know the library of pigeon books is small, so this trend of presents will dry up. The Queen, bless her socks, I discover likes pigeons too, and has her own pigeon loft at Sandringham, presided over by one Carlo Napolitano. The royals have been racing pigeons since 1898, and the Queen is patron of the Royal Pigeon Racing Association. And I think, I’ve never seen a picture of HRH with her birds. I wonder why?

“Pigeons from the Royal loft were used as carrier pigeons during the First and Second World Wars,” I’m told by the website, “with one bird winning the Dicken Medal for Gallantry for its role in reporting a lost aircraft in 1940.”

I find Napolitano’s email address, and start a correspondence with him. It turns out he is charming and approachable man. We progress to poetry about birds very quickly. It’s his wife who types the emails – he says he can’t bear to face a keyboard, after a day holding soft, trusting birds. I can sympathise with that.

He reminds me that Noah first let a raven to go find land, and that swarthy and unreliable bird never reported back. It was the next bird, the pigeon, that brought the olive sprig back to the boat.

He tells me that, did you know, results of the ancient Olympics were delivered by pigeon. A bird arriving in your town with feathers dyed purple, meant your man had won. Cue celebrations.

And I remember one bird, all pale sooty grey, with one purple tail feather, arriving in a box on my desk. Intella said, “Oh, lovely.” What did the coloured feather signify? It was on Frank’s birthday (which is also V’s).

And further, we are lead down some surprising avenues of connection. Mike Tyson the boxer, I am astonished to learn, was a placid eleven-year-old, until a local bully killed one of his pigeons. Tyson immediately exploded into an unstoppable beating of the older boy. He still keeps pigeons, they say around 350 of them. There’s a picture of Tyson holding a white dove (it’s the same thing as a pigeon).

In all this, I (and she) never consider any ad copy revolving around pigeons – apart from dropping that word ‘squab’ in, just once. But the pigeon stuff comes from a world too distant. And too precious. So that’s fine.

*

A bird in a box, with a script for GivingLiving:

THERE’S NO POETRY IN RETAIL

BUT AT GIVINGLIVING WE

– THAT’S YOU AND US –

COME AS CLOSE AS IT’S POSSIBLE TO GET.

AND IF YOU GET THAT, DO COME IN

AND COMPOSE THE PERFECT GIFT

TOGETHER WITH US….

[Thence into the details of the current special]

GIVINGLIVING

GIFTS THAT MAKE YOU

FEEL GOOD ABOUT YOURSELF TOO.

*

But the bird, that exquisite first bird, stayed in my mind.

It had headed directly out to sea.

I did some research: How far can pigeons fly? A pre-metrics book says they can average around 60 miles an hour, with burst of 110, I learned. Their total range, non-stop can be up to 300 miles. But usually, one way.

So, it wouldn’t cross the Pacific, would it? No.

And then it dawned on me – the bird wasn’t going to Tahiti or Chile, it was heading for Barrier. The last island for thousands of miles in that direction. Great Barrier Island.

That bird, the other birds – and the writer – must be from there. Great Barrier Island.

Of course. I should have known.

*

A script for a new Photoshop product:

ARE YOU ONE OF THOSE PEOPLE

WHO LIVE

IN A STATE OF PERPLEXION

THAT THE WORLD HASN’T DISCOVERED YOUR GENIUS YET?

WELL, PERPLEX NO MORE.

THE GENII IS OUT.

WITH webPHOTOshop THE WHOLE FRIGGIN’ UNIVERSE WILL SOON BE

ABLE TO KNOW.

AFTER THAT, IT’S UP TO YOU.

AND GUESS WHAT?

THE WORLD WON’T GET ANY MORE FAIR

ON UNDISCOVERED GENIUSSES.

THAT’S JUST HOW IT IS.

BUT IN ALL THIS UNFAIRNESS

webPHOTOshop

IS YOUR UNFAIR ADVANTAGE.

AND YOU DON’T KNOW THAT.

BECAUSE YOU HAVEN’T BOUGHT IT YET.

SO, YOU KNOW WHAT TO DO.

*

Once, when I needed one desperately (and somehow knew that she knew), the chocolate-coloured messenger arrives outside of a box.

Intella proudly does the ceremonials. I think she prefers this kind of live delivery. She says she likes the warmth of the just-arrived pigeons, their heartbeats subsiding from 600 per minute (in fast flight) to 200 (at rest).

I start to divest this bird of its message, Intella leaning over me. Her breath has the scent of almond croissant, her favourite breakfast (was V’s too). It’s pleasant.

Before unrolling the bird’s flimsy, I look up at Intella, not unkindly, just steadily. OK, she gets it. She retreats.

The note reads:

In a box could have been the answer to your

Lexus hybrid coupé image problem.

Especially after the Top Gear thing.

The words – the perfect words – are here. On my desk.

But, bugger it, why should I make things all so easy for you?

Like they say: Some days you’re the pigeon,

Some days you’re the statue.

So you’re on your own, this time, dear statue.

But the bird could do with some exercise.

Usual story,

Love,

Me.

I wondered what that cryptic ‘Love’ meant. I could construe it as patronizing. And ‘statue’? I think, inexplicably again, she must know about the peculiar state of love (or the flight version of it) that exists between me and V. And my paralysis about being able to do anything about it.

But not for long: I was too busy having to do my own writing, this time.

With my recent training, I got on top of the Lexus problem quickly enough. I had re-found the language. And sure enough, the campaign worked, Lexus was voted back into the top three luxury cars, in uneasy company with the new Skoda. How the world has changed.

After the Lexus work, I feel I could use a trip away. And I could happily investigate again what ‘Love’ meant. Even on transparently thin paper, and in the form of a patronising salutation at the end of a cryptic pigeon-borne message. So I go.

Only it takes three more months to find the time to be able to do it.

*

More scripts arrive, all good.

Then a third bird, the same chocolate redeemer, arrives on its own. Flimsy says:

Don’t take on new dairy conglomerate client.

Dodgy as.

Rivers, and birds, will thank you.

Reminder to soul:

Dawn needs no money.

And I broach this to Mark. He frowns (Yeah, OK, cheap trick, I know, but he does frown frequently, and that’s nothing to do with his name.)

“I was having my doubts,” he concurs. “Something not quite fluffy ducks about it…”

And sure enough, due diligence reveals the simmering scandal that brings them down a few months later. And like she said, the rivers and birds probably will be thankful that happened.

It’s only years later I can tell him the tip was in a flimsy.

*

“It’s as easy as it was for Bobby McFerrin,” she writes philosophically in one note attached to a script. “There is no magic in selling, when people are so needy. But I suppose everyone needs a hobby.”

And surprisingly, I know what she means – about Bobby McFerrin, the avant-garde jazz singer, he of the remarkable acapella polyphonic effects, who when challenged to make a pop hit said, easy, and wrote Don’t Worry, Be Happy. And then never debased himself in that way again. (And incidentally, never sang the song again after a George Bush election campaign appropriated it without permission.)

The scripts occasionally come with an additional note. They’re all short, often cryptic. But through them, she displays a great deal of knowledge about me. I begin to get supernatural vibes, but then just as quickly, shut them down. After all, I was the one who wrote the famous ‘Yeah, right’ line. On my own. Before her.

But who is she? How does she know so much? And why about me?

I even ask my Mum if there’s perhaps some adopted out baby in our family history. Some unfortunate teenage pregnancy, lopped from the official family tree. Some sibling or cousin or aunt out there, knowing me, unknown to me.

But Mum just looks at me quizzically and says, “Really, dear!” and that’s about all she needs to say.

Further mystery is added when a pigeon box brings a miniature pencil drawing of a close up of an eye. A right eye. I put it in a matchbox-sized frame, hung directly under the Magritte print, and in counterpoint to its scale. G thinks it’s gruesome. “When are we getting the other eye?” But it never comes.

But how does she the pigeon lady know, for instance that I like Tom Waits? (because I can sing along and still sound better than him – she even uses this tired self joke about me), and concept albums by Ry Cooder, presented as books. That I’m a sucker for corny music? Harry Belafonte. The Everly Brothers. I suppose it doesn’t take much prescience to guess that I hate (even boycott where possible) shops playing Christmas music.

That I write poetry, but don’t read it myself. That I skip over the poetic inserts you find in some novels. That I read too fast. That I’m the world’s worst proof reader, and proud of it. She calls me “vain-lazy”. It’s a phrase that sums me up, I think.

She even includes a line from one of my poems (never published), to make a point in one of her notes:

To set all shimmering this luminous load;

To live ardent-hearted;

And love it laughs like all our yesterdays.

She adds she does like my self-pinned label ‘ardent-hearted.’ And I feel puffed up, like a kid, with this rare approval. This stuff I don’t mention to Mum. This stuff stays out of the stories with the kids.

Like when she says in another note:

V will – someday.

She remarks on the irony of Iceland becoming top of the Human Development Index, just months before their economy melts down. I try hard to find the connection – but it must have something to do with our new financial services client:

LET’S GET REAL.

OLDEST RULE IN THE BOOK.

HIGHER RETURNS MEAN MORE RISK.

SO, IF YOU”RE UP TO IT,

COME RISK SOME MONEY WITH US.

FOR AN EIGHT PERCENT RETURN. OR ELEVEN.

YOU CHOOSE.

AND WE KNOW YOU WON’T PUT ALL YOURS IN ONE BASKET.

FAIR ENOUGH.

OR WHINGE, WHEN, OCCASIONALLY,

IT DOESN’T QUITE WORK OUT.

BUT MOSTLY, IT DOES.

Etc..

We shat ourselves before presenting this. Mark said, yes, we’d go with it, with no back-up concept. Big balls call. And guess what? It worked.

She knows I have a hobby (mostly in dormancy) of a collection of logos that feature birds. She sends me links to a few more. And in the course of this, because of this, we find a new client. Kingfisher Beer, used to be brewed in India and imported for the local Indian restaurant trade. But the growth of this – and also of the immigrant Indian population itself – means it’s now made right here, in Pakuranga.

IT TASTES BETTER THAN IT DID BACK HOME.

BECAUSE THE WATER HERE IS CLEANER,

…begins her script on this one. Chalk up another winner for the new reality.

The Kingfisher Beer logo is especially splendid, and is duly added to my collection. As is the medal we win for the ads.

*

I had half expected after the Lexus thing, and the being left on my own, that the birds would dry up. It took three weeks for another to appear. Intella was actually excited when she brought it in, and actually stayed for the launch for its homeward trip.

She (Intella) gave a little gasp of awe, as the bird took off. That moment, it seems never loses its magic. Especially for me.

I was feeling so benevolent, I bought Intella lunch at Hammerheads. I found a seat facing the Gulf, and the Island beyond.

Intella told me her dreams of becoming a writer herself, someday doing the Manhire course, but in the meantime she had an ageing aunt to support and nurse in her declining years. (I would never have thought this of her). Her parents had both died, she said, in the tsunami at the resort in Samoa.

*

More birds came. And I found the time – seeing my copywriting was being done for me – to re-visit the stories. I found they weren’t half bad. Worth working on. And so the manuscript blossomed, was completed. It had a uniformly positive review from a manuscript assessor, a literary luminary. But found no publisher.

I even had a title suggested by the pigeon woman. (I’d stopped wondering how she would know.) But the colourless title I’d given the collection, Two, became jesus of the credit cards, the title of one of the stories. It had a nice ring to it.

In parallel I thought I’d resuscitate working on the novel. But which one? I had started three. They were about

- a Brazilian volleyball player, who was reluctantly chanelling the voice of a priest who died in disgrace in Tete in the seventeenth century;

- the turning of the earth inside out, a kind of geological emergency, uniting in the common cause of combating this. This a backdrop to a love story; Called The Folding;

- the re-colonization of the Kerguelen Islands by a misguided and dysfunctional group following a charismatic conman leader. This in the 1980s, long after colonization had gone out of fashion.

In the end, I chose to pursue The Folding. It’s now up to 60,000 words, going well.

*

I figured out how to attach messages to return with the pigeons; and tried it once.

I agonised for hours on striking just the right tone with my introductory missive – taut, worldly, ironic, slightly supercilious, just like her. In the end I thought I had a haiku worthy of its mission. It read:

Hi –

No pressure,

but would love to know more about you.

And how you know so much about me.

And to thank you for the words

that work

(surprisingly)

so well.

Mark

I struck out.

The feedback received with the next bird was painful. I won’t share it with you – a story-teller needs some secrets – suffice to say she honed in on my weakest spot, acerbically. I thought I was robust, ego-wise, but she sure knows how to get to where it hurts. More than V, in fact.

So my tiny little aluminium tubes for the Barrier-bound flimsies stayed in a top drawer. The minute squares of rice paper were given to the kids, with and elaborate story-game about secret drawings. Holly, in particular took to her new hobby.

*

And, apart from the odd, cryptic card, I never hear from her, the other her. Nothing substantial in communication. V, that is. Although the credit card keeps hemorrhaging, mightily. Mostly from the northern hemisphere, Europe, sometimes the Bahamas. Once, Belize. I have to look it up where that is. And always expensive stuff. (In Belize the money went mostly on the hire of a 4X4 from Avis. Yeow! They knew how to charge, but I suppose when in Belize…) Once, a swag of expenses from Namibia. Couldn’t she eat cheap, dress cheap, travel cheap, just for once? Just for fun?

And I started thinking, perhaps I could shut the thing down, why not? I should really. But I didn’t – the entrapment of chemistry, I suppose. And hope.

And how about contacting me? This can’t go on forever. And I don’t imagine it will. We will look back on this just as a chapter, and someday laugh again. But right now this one chapter feels as long as The Lord of the Rings.

The kids, Holly, Hazel and Frank, me, and my Mum, we all got used to the new regime. We almost got into a routine again. With at least the levity of the pigeons added to the mix.

And the house kept sliding, imperceptibly.

I had a dream it was the added weight of a single feather that sent us all over the edge and splashing into the harbour; and woke to find Frank (the dog) snoring in my bed, and the advertorials on a TV that was still on.

*

So I finally get to Barrier. The five-hour trip on the Eco Islander ferry is a colourful ordeal in itself and I’m thinking the weird assortment of passengers, and our circumstance would make a great play. (Very drunk local to family of American cycling tourists, brave mum, tense dad and seasick eleven-year-old daughter: “You look like wankers in that lycra. Yous need swannies.”) For another time maybe. Our late-night arrival doesn’t make things easier, but somehow we get Mum and the kids tucked up in a bunk room at the Possum Lodge. I leave early, before they are awake.

*

What do I find?

I find the pigeon woman. It’s not that hard to track someone down in a community of only 600 people. Even if most houses out here are hidden in regenerating bush. Even if some folk wouldn’t want to be found. Even if there is no road to this property. Even if there’s no phone.

But I know I can arrive unannounced. The last pigeon note predicted I’d come – even down to this day, on this weekend. I’d come to expect this. How does she know these things? Come to think of it, how do I know she is a she?

I must walk for an hour to get to her place, from where some hirsute and laconic bloke with a ute drops me.

He doesn’t say much, just points down a track, to the shore at the bottom, and at the bay beyond. A sparse, yet eloquent gesture. He flicks a finger in farewell, and slides off downhill and around a bend in a spray of gravel.

For the first time, quiet envelopes me. Then a tūī starts to sing. I start walking. The stolid flight of a kereru across the valley catches my eye – I follow it labouring like a Lancaster bomber (I was a childhood fan of the Dambusters movie), and this leads my vision to…

…above me, a flight of around a dozen homing pigeons is wheeling, as if flying just for fun, their wingbeats athletic and effective compared to the lone native soldiering on below them. They bank in graceful unison – it’s a profoundly beautiful sight, and my soul swings with them (and incidentally, I suddenly understand the appeal of keeping racing pigeons, and understand why, apart for the Queen and Elvis, it’s generally a sport that is the preserve of the ordinary working man) – and then they descend rapidly, as if they can let go of the air anytime they like, like you or me dropping a bus timetable.

And of course, they mark the spot. I know where to go. But then, I think I knew all along…

*

It seems she does, too. She appears to have been expecting me. She is standing in the doorway of the house.

She simply says my name. Then her name. Which is Mallory.

“Two ‘l’s. Which means unlucky.” An almost imperceptible shrug. “You decide.”

She nods slowly, deeply, as if in benediction. Her eyes hold me resolutely, but calmly. I for once, I don’t squirm at this.

Her voice is warbling and light. I know I’ll kick myself later, when writing about this first encounter, because I’ll say her voice has that sub-musical quality of pigeons’ conversing. And I know it will sound as corny as this just has. But, hey, I’m starting to think I’m as lost here, as V is…wherever she is now.

Mallory’s greeting is unexpectedly easy, gracious (I had expected some kind of hermit), but with some distance kept (Aha! – there at least, is something I can predict!)

She shakes my hand. Then – surprisingly – tousles my hair. And I don’t even move. Odd, for me. “The birds call me Mal,” she says.

What does she look like? She’s tall, trim, muscular, and surprisingly un-withered. I had expected some sun-wizened hippie, living out a life of fragrant regret, of missed chances, of the world un-repaired by herself, but yet in the fortunate seclusion of this place. But no, she has a brisk air about her.

She is ageless. I could not begin to guess at her age. There are years there, for sure …she is older than me…Her eyes could be those of a benevolent aunt. But then why do they feel so intimately familiar? From that miniature, once delivered by pigeon, perhaps? No, surely not. And that was only one eye anyway. But, still…

She stands aside, and with a half turn as graceful as a dancer, soundlessly invites me in. As I brush past her, I take in the distinctive scent of the native jasmine, parsonsia. And it’s long past spring, so where did she get the flowers from? (This is something I’ve picked up from my Mum. She’s an avid gardener of native species, so I’ve imbibed this stuff from since I was young. And my senses are heightened right now, I’m using all my faculties to make sense of this, you can tell).

As I step in, I’m dimly aware of her stepping outside, soundlessly conveying to me that she’ll be back in a moment.

I circle awkwardly in the living room. It’s cool and shaded. Windows are flung right open, under the roof of an all-encircling porch. But there is something about it, something missing, something indiscernible, and it is different to anyplace I’ve ever been before. It’s comfortable enough, in a bach-vernacular kind of way – but I’ve been to plenty of these. It sports an untidy collection of books. But still, there’s something about the room that I can’t quite get a handle on.

Hang on, I find myself thinking, there’s something else odd about the place. And I reply in my own inner-head conversation, “But what else did you expect?”

I wander a few minutes more, destination uncertain, holding my gifts, my backpack still on. I idly brush my fingertips against a tabletop. I think to sit down, hesitate, then drift towards a window to stand gazing at a view of a cove framed by trees.

There’s still that something about the house. And then I see that the window… isn’t. There’s no glass, only a large shutter, clad in thin, overlapping boards, lifted up under the verandah roof. A meagre seabreeze tickles the heads of cabbage trees in the valley below, and brings a scent of rock pools to me. A gannet diving out in the bay catches my eye for a moment.

But still, there’s something about this house…So I turn again to take in the room.

Then the astonishing thing dawns on me. Apart from the books – and they all have a distinctly well-loved look to them – there is nothing, absolutely nothing else in the house that appears to be store-bought.

Everything, but everything, is home-made. Everything that is visible, that is. And I shouldn’t say home-made – rather hand crafted, for there many truly fine items. Each piece of furniture is an individualistic work of art.

Here is a place where our world of creating want, generating buying, the endless cycle of acquiring, discarding, simply doesn’t exist. And that, I realise, is what’s flustering me most.

But just then, she steps back inside, with hands full of salad greens, and this time followed by a dog, an elegant black pointer cross.

She sees my look, and smiles. (And I swear the dog smiles too).

She knows exactly what I’m thinking. “Ok, hey, so we cheated – we used some nails in the construction. And some fine steel tools.

“Some other things, too. We thought it was acceptable,” she says tossing the comment over her shoulder as she heads to the kitchen. Which, I notice now, of course has no whiteware, or any of that stuff. The stove is a woodburner, made from baked clay.

Aha! I think, I’ve caught her out. Her clothes! They must come from a factory.

Again, she anticipates my thought, and releasing the greens on the bench, steps closer.

A man’s shirt, and knee-length flared skirt, both quite stylish actually, are made from linen. “The fabric?” I ask, and she, knowing where I’m going with this, steps closer, so I can take a hem of her shirt between my fingers – and realise yes, it’s a linen, but hand-woven, and finely so, from flax fibre. Yes a linen, a lovely linen, but from no factory. Her eyes smile at my slow dawning, then her lips follow, smiling too. She says, by way of an incomplete explanation “Tanekaha bark makes for this reddish dye. And there are others. Nice, hey?”

And so we embark on a tour of this astonishing home. She explains everything lightly, not lecturing anything to me, but it become apparent that she has a deep and profound knowledge of materials – every item is melded as one with its constituent materials and expected purpose. I get the impression she’s made most of the stuff, but also that other craftsmen (craftspeople) have been involved in this. She often uses a ‘we’, again, lightly and easily. A hint of a smile lingers on her face all this time.

She shows me a weaving loom in an airy back room. It’s made entirely out of hardwood rods. “Kanuka,” she says, pointing at some pieces, “Pūriri,” at the bobbin, worn smooth and shiny. It’s where her fabric comes from.

The bottle of wine I have bought looks obscenely out of place. My hand holding it – originally stretched out with it as a gift, now seems exposed. That hand wilts, half scurrying around my back. I’m as awkward as the 10-year-old I used to be, bullied in the school playground.

She senses my mood, and hurriedly says “Oh, no! Don’t fret. I’d love a tipple.” She reaches out, takes the wine, and at the same time, with practiced expertise, pic-pockets me of my cellphone. She switches it off, and places it in a wooden bowl by the front door, smiling, direct eye contact, nothing said. I shrug helplessly. But, somehow, this is fun. It’s the purest gesture of hospitality I ever known – apart from the time my Mum served porridge for dinner to a visiting MP, who happened to responsible for social welfare, a friend of a friend – and carried it off.

And then she asks “Is that all you’ve brought?”

And suddenly I feel proud of my prescience in having the other bottles in my backpack. But, then, also, embarrassed about the pesto dips in their dinky little plastic and foil packages.

Her confidence, her easy manner, her un-adulterated joy of living overwhelms me. But I also know she’s playing me. And I also feel inadequate and stimulated in equal measure in her presence.

We go for a long walk.

We talk for hours. I try keep up. I’m reminded of an episode in my early university days, when…

Later, the driftwood chairs she steers me to on the verandah are surprisingly comfortable.

These are the easy chairs, for there are others, more finely crafted, from what I think is matai. She nods.

Sometime in the afternoon, another woman appears, Em, then a man, Don. And two dogs of indeterminate breed. Conversations stretch outwards, and at some stage, I don’t remember when, suddenly the visitors are gone. The dogs stay.

She shows me her pigeons. They are by now, friends. And they greet me as if I am too. I’ve learned that pigeons are good at recognising, and are one of only eight non-human species, and the on non-mammal, who can identify individual selves in a mirror. And Munts, the original Munts is there. I imagine he winks knowingly at me. It turns out he is wedded to the remarkable chocolate two-way flyer. Pigeons, we know, are paragons of fidelity. She doesn’t have to remind me of this.

Evening arrives. We must eat. But first, in the order of things in this world, we must first construct the meal.

We start with a walk, down to a rock pool. It’s a scramble down through bush on a deep-shaded path softly bedded with kohekohe leaves. We stand for a moment on a rock overlooking the pool with eyes closed – she does this, I instinctively follow, with no prompting, it’s like I know exactly what to do around her. Then she kneels lithely, and plunges her hand under a rock – a mid-size octopus emerges writhing on the end of her arm. “Been saving this for a special meal” she says, to me. To the octopus, “Sorry.” To me again, “Poor bugger.”

From a soft leather drawstring bag, she takes a superbly handcrafted pair of swimming goggles. I reach out soundlessly. She lets me see. I handle them in astonishment. My scuba diving background means I have some knowledge of what it takes to have something like this self-made. The lenses are thin sheets of smokey odsidian. The frames are a hardwood (heartwood pūriri I guess, and she nods), the caulking from kauri resin kept soft I don’t know how. Straps to tie around the back of her head are of springy blue-tinged penguin skin. They are a work of art. Just this one thing, amid everything that surrounds her. She slips into the water. I sit in stunned mullet silence. She returns with more kaimoana.

The dinner is the salad she picked earlier, with gooseberries as a surprising ingredient. The octopus flesh, marinated in a mead she produces. Scallops sautéed in a sauce of seawater and some of my white wine, garnished with the puha we collected on the way up the hill. Fresh new potatoes, acorn-size, delicious, dripped with a tangy olive oil. A desert from yoghurt with comb honey pieces and a peppery edge from a herb I don’t recognise. “Kawakawa,” she says. My wine complements it all well. By now I had come to expect this.

She shows me where she writes. I’ve anticipated the fine quill pens, the rich, thick handmade paper for the envelopes. She shows me how she makes the flimsies – same stuff really, just a way more delicate process. The ink? “Remember the octopus,” she says. “And some other ingredients.”

She shows me where I will sleep. It’s a hammock. I raise a questioning eyebrow. She just laughs, her pigeon chuckle, and says simply, “It’ll work.”

We continue to talk and talk and talk. By now, you can imagine what about. But she still doesn’t exactly answer my central question. Who are you?

*

I’m in bed. I know I will drift off soon, into the kind of un-troubled sleep I haven’t had for years.

What will I do tomorrow? Is my last thought. I know I will dream about her.

*

The phone rings, where it has been left in her in-basket. (The phone has an automatic ‘switch back on” function. It can’t bear to be left unused too long. Or is that, I can’t bear to be left alone too long?)

Whatever – the phone chirrups its cheery mock-rainforest chirrup. But it sounds garishly out of place here.

It’s answered very soon afterwards by a bellow of raw rage. It is my host. It’s not a pretty sound.

I tumble from the hammock, and rush to the basket. I can see the way clearly in the limpid silver moonlight that falls unhindered through the open skylights.

Mallory beats me to it. She is nude; and clearly enraged. She silently hands me the phone. The cold light of the phone screen illuminates her face from below. She becomes aware of it, and turns her face away, as if scalded by it.

The phone chirrups again, as if to compound the affront. She turns away and stalks back to her room.

I turn the screen to face me. The message says:

Hi, it’s me.

Run out of Europe,

but found myself.

Can I come home?

Have started sending stuff.

You’ll love most of it.

Kids too.

V.